In late January 2020, amid muggy Southern hemisphere summer heat, Melbourne’s Left Ear Records label made an Instagram post. They’d acquired some deadstock of an obscure Australian ambient cassette tape titled Picture Music, originally recorded three decades earlier. Intrigued by the artwork and the backstory, I ordered a copy. Several weeks later, I received a pristinely preserved copy in the mail. Haunting from the very first notes, Picture Music was an embarrassment of riches. That summer, I thrashed the tape on the stereo in the mornings and late at night, constantly in awe of the pictorial elegance of its dimly lit but richly atmospheric instrumental evocations.

Two and a half years later, Left Ear Music announced that after almost twelve months of delays, they’d reissued Picture Music in vinyl and digital formats. Revisiting the album was a delight, but it wasn’t enough to just listen to Picture Music’s heady concoctions of OST-style minimal jazz, ambient, and experimental music. I needed to know more. So, I did what you do in these situations and dropped Chris Bonato from Left Ear Records a couple of messages. Chris was happy to fill me in on what he knew and put me in touch with several people involved in or associated with Picture Music. From there, we exchanged a series of emails which served as the basis for this article. Sometimes you’ve just got to let the music take you where it takes you.

As the tale goes, the Picture Music story began in Brisbane, circa 1982, with the formation of a recreational jazz-rock big band with an interest in non-western rhythms, The Hollow Men. Emerging within an Australian cultural landscape dominated by chart pop, nostalgia hits, and pub rock, the musicians who played in The Hollow Men had open ears. They were searching for something different, jazz fusion, ambient, minimalist composition, anything on the edges. Sometimes, they found it in the record bins at Brisbane’s Rocking Horse Records or through friends returning overseas from London and New York. Other times they heard it on the radio through the local indie station 4ZZZ or in the soundtracks of arthouse films screened at the University of Queensland’s Schonell Theatre. Weather Report, Brian Eno, Steve Reich, the cult Bulgarian folk album Le Mystère des Voix Bulgares, the list went on, and it still does.

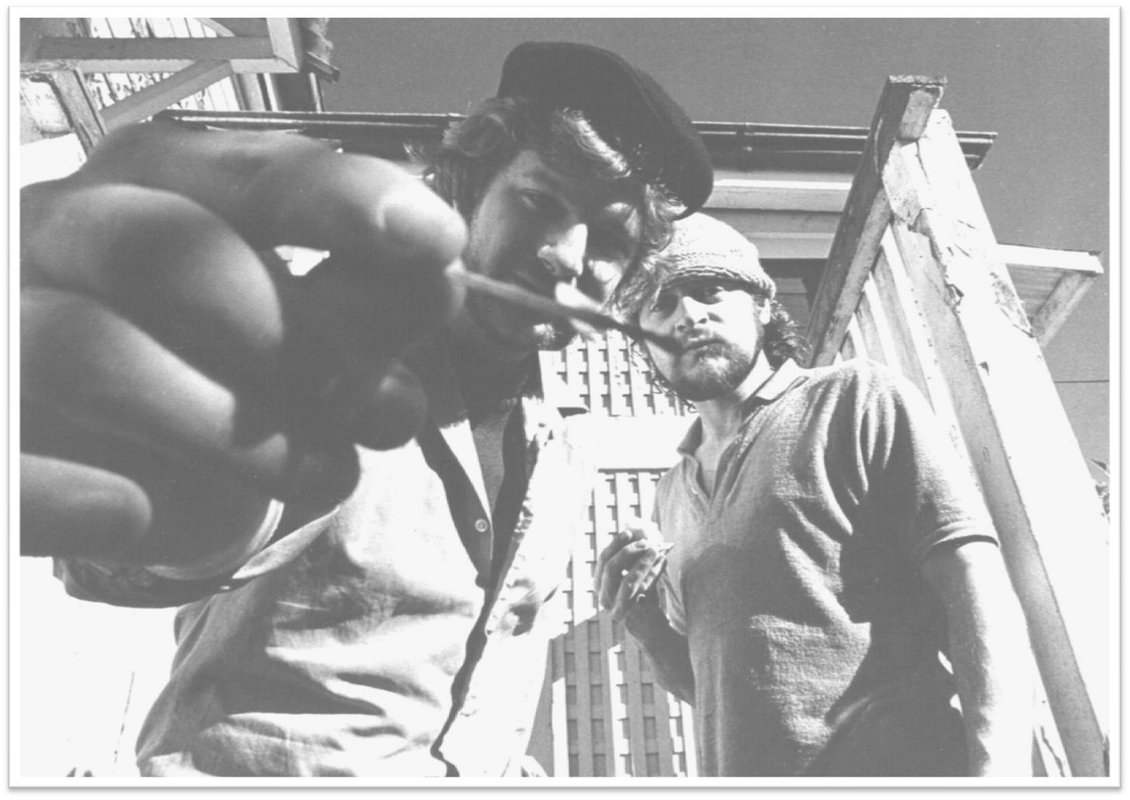

More than just a band, The Hollow Men also served as an informal social club for a group of musicians with common fascinations that sat well outside the pub and football club culture of the era. The band and their associates would gather for rehearsals, conversations, and general merriment at a house at the end of Graham Street in South Brisbane. That particular address was the residence of two band members, Rainer Guth and Peter Walters.

Rainer, who sadly passed away in 2016, is described by those who knew him as a larger-than-life character with an infectious sense of humour and an enviable record collection full of European and American jazz with a strong ECM flavour. Jan Achurch, who married Rainer in 1995, remembers him as a deep thinker on the human experience who didn’t like being called a musician. “Rainer was very sensitive to ambience and so very good at judging the right music to create a mood,” she reflects. “Sound generally was exciting to him.”

Photo: Peter Walters and Rainer Guth (Barry Swan collection)

During the early to mid-eighties, filmmaker and musician Gary McFeat was employed by the University of Queensland’s television studio to handle camerawork, editing, sound recording, and mixing duties as part of the production of educational videos. In 1984, when Gary was commissioned to make a short promotional video for Brisbane’s municipal transport authority, Rainer produced the backing track. Recorded on a 4-track reel-to-reel recorder in the living room at Graham Street, ‘Bus Stop Dawn’ was a collaboration between Rainer (guitars), Peter (double bass), Jon Anderson (Casio keyboards). A blend of elegant guitar notes, neon-lit keyboard melodies, and cloudy synths, it eventually became the first track on the Picture Music album. In a sense, ‘Bus Stop Dawn’ serves as an invitation into the overarching aesthetic followed.

“This was the [Premier] Joh Bjelke-Petersen era, so political and social conservatism, politicisation of the police force, and corruption in government were the order of the day. I guess this led to a degree of disillusionment and cynicism with mainstream society, which lead us to explore unusual outlets and not be too worried if our efforts didn’t reach mainstream acceptance.”

Jon Anderson arrived in the equation through his friendship with The Hollow Men’s keyboard and piano accordion player, Gary Nunn. Both attended Queensland Teachers' Training College (then Kelvin Grove Teachers' College), where they studied to become music teachers before opting for musical lives outside education. Jon made pizzas and played the piano at dance classes around Brisbane. Gary was in an ethnic-fusion band and won piano accordion contests.

Like the rest of the circle, Jon was a deep music head. However, his interests lay in shortwave radio and early electronica recordings by Tangerine Dream, Frippertronics, Kraftwork, and Manuel Göttsching. Between Jon’s records, the African pop, Indian classical, and post-punk in Gary McFeat’s vinyl collection, and Rainer’s ECM bins, they had a rich palette to draw from. “None of us really listened to Australian music, particularly Aussie rock that I’m aware of,” says Jon Anderson. “We didn’t go out much. If we did, it was to friend’s jazz concerts or the very rare international act.”

“This was the [Premier] Joh Bjelke-Petersen era, so political and social conservatism, politicisation of the police force, and corruption in government were the order of the day,” explains Gary McFeat, as he reflects on the conservative social context that hung over them in eighties Brisbane. “I guess this lead to a degree of disillusionment and cynicism with mainstream society, which lead us to explore unusual outlets and not be too worried if our efforts didn’t reach mainstream acceptance.”

Alongside the parallel musical universe they shared, most of the musicians also loved cinema, and film nights at Graham Street were a common occurrence. With the rise of major Australian film studios on the Gold Coast a few years away, the Queensland film industry was mostly made up of a small number of independent filmmakers. As a result, there was a space in the market for locally produced music for television, movies, and adverts. After successfully producing a couple of tracks for video projects, the musicians began to envision a future for themselves in soundtrack work. Enter Picture Music.

“Listening back to the album now, the music is inextricably woven into the late night ambience of that smokey shadowy room, as if we inadvertently made a soundtrack to our nighttime lives.“

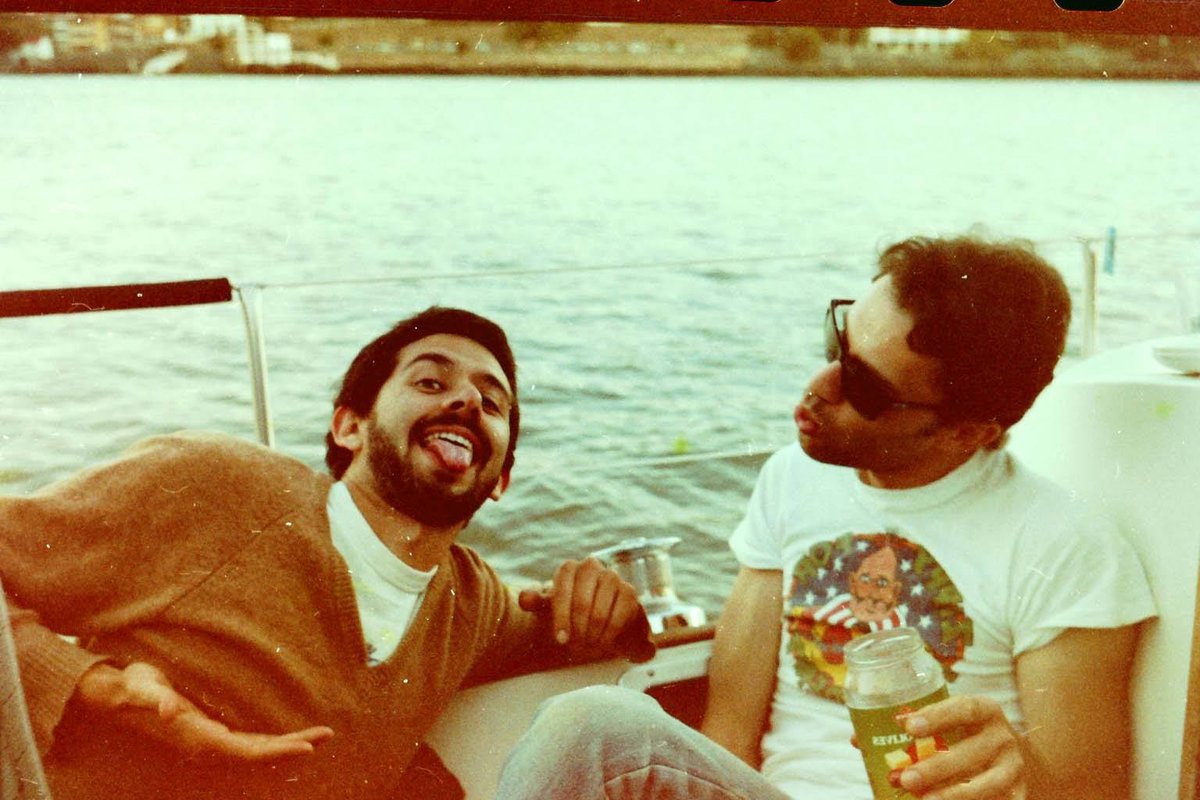

Photo: Rod Owen and Gary McFeat (Peter Swan collection)

Over the next couple of years, the musicians continued recording between two locations, Peter and Rainer’s Graham Street house and a flat shared by Gary McFeat, guitarist/bassist Rod Owen and Jon on the top floor of the Queensland Theosophical Society. Crammed full of musical instruments and gear, the Theosophical Society became the scene of countless all-night jams, with the best results documented on a Tascam 4-track PortaStudio.

In many ways, the mid-eighties was a fertile time for developments in music technology, several of which, including the Ensoniq Mirage sampling keyboard, digital delay pedals, and the Ensoniq ESQ-1 digital wave synthesiser, allowed them to take their craft into remarkable places. In response to Brisbane's excessive heat and the lack of air conditioning at Graham Street, the musicians generally recorded between 8 pm and 5 or 6 am by candlelight.

“Listening back to the album now, the music is inextricably woven into the late night ambience of that smokey shadowy room,” explains Jon Anderson. “[It was] as if we inadvertently made a soundtrack to our nighttime lives. What it was like is how it sounds. Casual conversation in quiet tones, the ashtrays, 12-year-old single malt whisky, cold beer, cigarettes, good weed, the incessant sounds of crickets outside the windows, the warm, smokey humid night ear, the peeling wallpaper, the worn seats and sofa, the candles and dim lamps, which somehow always seemed to produce more shadow than light.”

In 1986, Rod registered Picture Music as a business after discussions with Rainer, Jon, and Gary McFeat. Their next step was manufacturing a cassette tape of their recordings to shop around to filmmakers, film, and television production companies, and agencies as a showreel. In 1988, they duplicated five hundred copies, anointed the Bill McMurty-designed cover with a moody image created by the Brisbane visual artist Colleen St. Ledger, and sent the Picture Music tape out to the industry. Although copies of the tape were also made available for purchase through Rocking Horse Records, sales were limited. And for a time, that was that.

“Tapes can really expose another universe. You’d think this continent’s music had been completely exhausted until someone fatefully finds a cassette of celestial lullabies and folk minimalism on the side of the road, ready to go in the most perfect cover art. That’s a fantasy of any record label.”

Three so decades later, Rainer’s daughter left a box of his old cassette tapes out on the street for kerbside collection. Before the rubbish truck could get to it, the box caught the eye of a local music collector, who swooped it up and sold the cassettes to Phase 4 Records in Brisbane. A couple of weeks later, Chris Bonato from Left Ear Records dropped through the store on a digging trip from Melbourne. As Chris Bonato remembers it, “I saw the tape on display and asked to hear it. After a few seconds, I was sold.”

From there, Chris began contacting the Picture Music members to arrange to reissue the album. Several years later, the project was pressed up vinyl and began circulating the world in the manner it always deserved to, along the way finding fans in heads like Smiling C, Séance Centre, Mori-Ra, and Efficient Space. “Tapes can really expose another universe,” muses Efficient Space boss Michael Kucyk. “You'd think this continent's music had been completely exhausted until someone fatefully finds a cassette of celestial lullabies and folk minimalism on the side of the road, ready to go in the most perfect cover art. That's a fantasy of any record label.”

“I'm completely baffled by the weird contrivances of good fortune that would have led to our humble little cassette seeing the light of day after all these years,” reflects Jon Anderson. “It feels a bit like having the YouTube algorithm embrace your strange, funky, neglected, half-forgotten channel, propelling it out of obscurity and into a broad public eye for no apparent reason.” That’s the thing, though, as the Picture Music story illustrates, no matter how random it seems, there’s always a reason. Sometimes that just means a whole bunch of things have to go wrong before something else can go right. It’s a funny old world.

Picture Music is available for purchase in digital and LP formats through Left Ear Records (here)