Warriors Dance

An Interview With Kid Batchelor

Next up in our trilogy of interviews with the key protagonists of the Warriors Dance label, London house trailblazer Kid Batchelor goes deep.

Can you tell us a little about your background?

I've been playing records now for 30 years. The first liquorice black discs I learned to DJ with were seven inch and back then we were mixing it with disco. I was obsessed from an early age. I loved the smell of vinyl. And I'd be taking in the artwork too, which made me realise that the music was about much more than what you heard and that made me interested in the business. There was a legacy in place. So, hours of fun. With this admission of idealised nostalgia for the non-digital age, it's no surprise that I was especially taken with breaks and beats to gain the perfection of that Turntable Science. I sank into hip hop culture like a hot bath.

Pirate radio stations were big for me in the Eighties. Before so called “intelligent drum and bass” – with superstars like Jazzie B, Trevor Nelson, Lisa I’Anson, Dereck B, LTJ Bukem, Goldie and so on – there were pirate stations such as JFM, Kiss, LWR WBLS Tuff Audio and Contrast Radio.

They were put together on the fly – illegally – using broom handles as temporary aerials. Pirate shows were chaotic, fast, loud and the most exciting thing I'd ever heard. Intimidating and dangerous, the scene was my generation's “punk rock” in many ways. The energy though was undeniable. My body was at home in Kings Cross but my spirit was in a smoke-filled room in south east London, raving to Froggy the Funkmaster. As a younger man I couldn't wait to go to the Lyceum in the Strand and strut my stuff to the first real superstar DJ Steve Walsh – who died in Ibiza at the height of his fame. I also listened to Greg Edwards, Robbie Vincent and Pete Tong on Radio London and Capital respectively, and John Peel in BBC Radio 1, occasionally.

I've always been a flash git. I was an unfortunate looking teenager. And, like many awkward young men, I took up martial arts. I wasn't interested in fighting. The appeal lay in strength. I wanted to feel strong. Other guys my age who were a bit broader provided envy in me, and although I trained for years, my bony physique refused to morph into something heftier. Three decades later and I'm still all elbows, but I couldn't care less. Kindness, empathy and wisdom are strengths, too – ones I at least have half a hope of training.

I'm sorry this has become a bit confessional?!

Was music a big part of your early life? What kind of music was around you as a child and what do you remember making an impact?

Family, identity and the power of roots rock reggae music then. The Caribbean sound defined London in the early Eighties. It was my first introduction to music and had a huge influence on what it means to be black and British today. The lineage has travelled all the way from then through to UK house, garage, jungle, drum n bass and grime.

As the Windrush generation came here, they worked hard to integrate while establishing a community and keeping our culture alive. The fruit of that was us becoming a huge part of not only the black experience but also the immigration experience in the UK, and the music was the backbone to it all – it soundtracked being in this country.

I was surrounded by music growing up. If you love vinyl, classy speakers and hi fi gear with sexy knobs on you, my friend, are an audiophile. “Keskedee” was a major hang out come youth club, where we built homemade bass heavy speaker sets and DJ equipment. There were as many Jamaicans in London in the '70s as there was every other islander put together – and they had the sound systems. Plus they had the culture of putting on dances and selling tickets and drinks. And from the end of the '50s they had ska from back home, which then developed into rocksteady and reggae. Before that, black British music was more about jazz and US R&B, but the sound systems moved Jamaican music culture to the fore in London. As well as jazz, African (afrobeat) music there was a genuine love for reggae, ska, and soul – it was a real melting pot. “If this world were mine, I'd play rub-a-dub all the time.” At family parties, I remember records such as Junior Marvin’s falsetto Police and Thieves (in de streets) and Smilie Culture Cockney Translation being played and those sounds eventually infiltrated my tastes when I started buying/playing records.

Even now there are still samples in tracks that remind me of music I heard at those family parties. So there's been a natural progression from the music of that era when we were kids into the music that resonates with black Londoners today.

It looks like you were very early into house music. Where did you first hear it and what did you think?

My house inspiration

In the mid-to-late-Eighties, London was a rare groove paradise. But up North it was different. It featured iconic post-industrial design. There was no dress code. And the music played inside was an impossibly cool, mould-breaking mixture of hip hop and electronic dance music that would provide the spark for the Acid House musical movement. DJs in the midlands readily adopted the new sonic styles. Birmingham’s Koolkat, a label which also released much Detroit techno on these shores, released my first jam, Glad All Over.

I recall one NYE in Bristol, a Soundclash: Soul to Soul and The Wild Bunch. Hosted by local turntablists The Wild Bunch (DJs Nellie Hooper and Milo) incorporated house music alongside their break beat, scratch-mix style. I knew house would dominate for years to come.

Meanwhile across the Atlantic mastermixers (Tony Humphries, Timmy Regisford etc) provided a golden age of creativity on air and on dancefloors. The creativity of the time stemmed from the freedom of radio DJs to play what they wanted. Frankie Crocker helped open up commercial radio to hip hop, broadcasting the sounds of the underground DJs throughout the five boroughs. Mixing was also introduced at this time, as radio DJs like Tony Humphries and Merlin Bobb, Timmy Regisford and Boyd Jarvis (Saturday Night Dance Party, WBLS) and Mr Magic turned their airtime into full, seamless soundtracks, where one song effortlessly blended into another. “You're expressing emotion and you're receiving it back” said Merlin Bobb, “even if you're not in the club and you don't see it.”

Humphries (him again) even created a house music sub-genre ‘the Jersey sound’ which was very soulful. Back to the city of my dreams, the late Colin Faver was at the vanguard of house and techno as they burst through in the late '80s and early '90s. He championed the most cutting edge music as rave exploded and his Kiss FM radio show was hugely influential (I was a friend of the show).

Did you get a lot of resistance from your fellow soul DJs when you started playing house?

Safe to say, the Big Smoke was not an early adopter – Stallions, The Jungle and of course Delirium at Astoria, one of London's early house nights (run by Robin King and DJs Irish brothers Noel & Maurice Watson) notwithstanding. To paraphrase Godfather of house Frankie Knuckles: ”they wanted to hear James Brown and anyone who had played with him”, they would not suffer the body being jacked and they had a strange aversion for four-to-floor beat?

I however moved away from super heavyweight funk to embrace the newer club sounds coming out of America. I became among the first UK DJs to play and make house music and held down a west End residency, Confusion, putting Warriors Dance at the heart of the acid house explosion, which inspired so many well known creatives (too many to mention here). And that was house unplugged, unleashed, as London prepared to have its chakras blown wide open. When acid house arrived changing the night world forever I was there, on it. I played at meccas from Shoom to Haçienda, as well as raves such as Biology and Sunrise, etc. I even played proto techno workouts at the Africa Centre, Covent Garden on Sunday night – eg Strafe/Harlequin Fours Set if off, Nitro Deluxe Let’s Get Brutal, Two Puetericans Do It Properly. Daryl Pandy performed Farley Jackmaster Funk’s Love Can't Turn Around Live – but London's club scene was still in the grip of the retrogressive rare groove revival despite the best efforts of a handful of forward thinking DJs who'd already been playing the new Chicago house and New York Garage tracks for two years, among them the late Colin Faver and Eddie Richards, whom took me under their twin wings.

The warehouse party scene of mid 1980s London happened typically in Kings Cross, Shoreditch, Camden Town, Waterloo and London Bridge; frequently decaying but easily accessible inner-city locations imbued with bleakly romantic post-industrial wasteland chic, a frisson that added an edginess. A milestone in house scene development was Hedonism, which began in February 1988 in a warehouse in Hanger Lane, of all places.

It was already a year since Farley Jackmaster Funk and Daryl Pandy Love Can't Turn Around, Steve Hurley’s Jack Your Body, had taken Chicago house into the UK charts. UK acts Marrs Pump Up The Volume and S Express had chart success too. But despite these and a handful of other crossover hits, house as a club music phenomenon in the UK remained a niche underground scene limited to a small number of clubs in cities like Manchester, Sheffield and Nottingham. But by the time the needle was lifted on the last record at the final Hedo all-nighter session just three months later, the U.K. was on the brink of the biggest music revolution in decades. For me, at that time Europe carried the swing; it had the style and scene I craved.

How did you meet Tony?

The London music scene was a hotbed of creativity. We found each other.

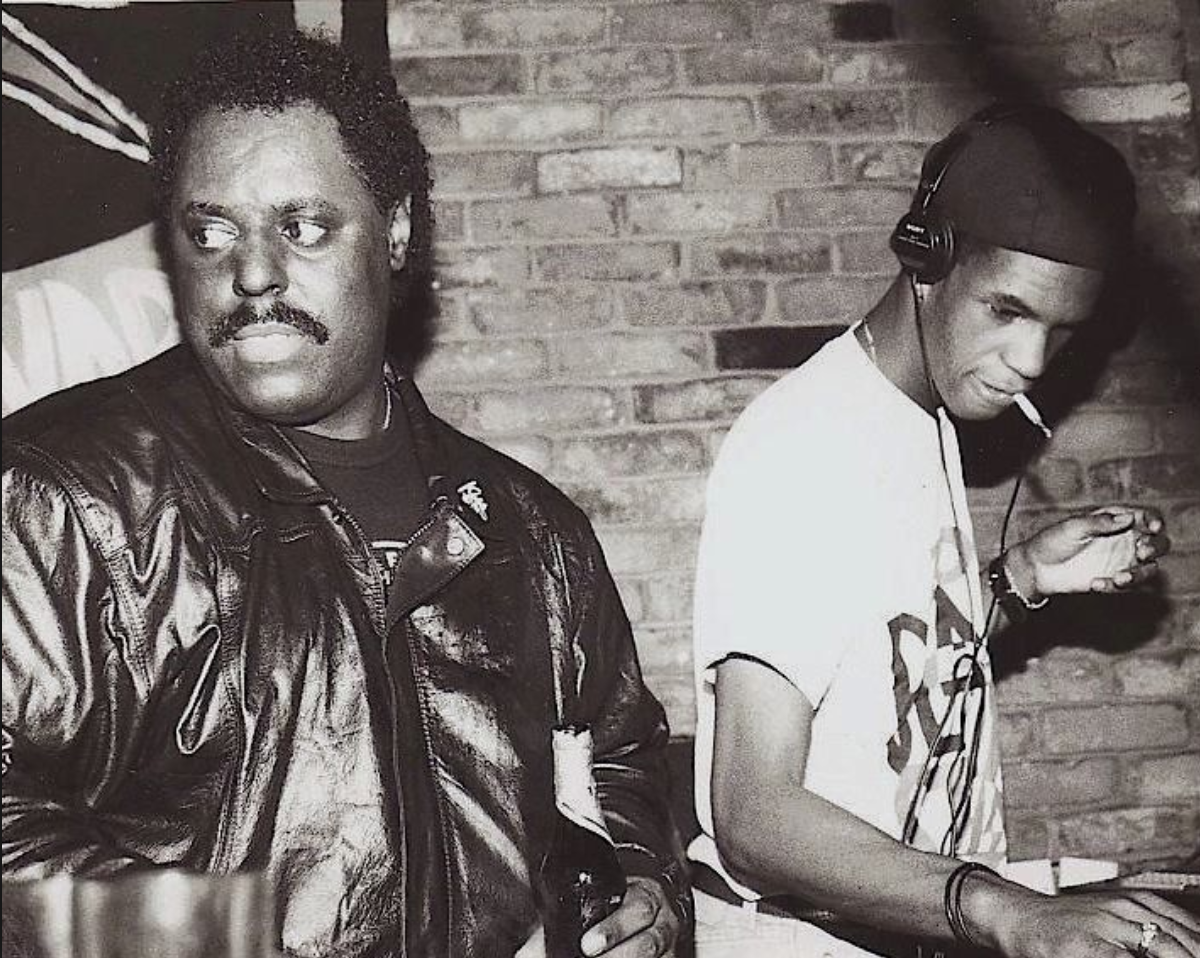

The story goes... Warriors Dance Records launched in 1987. Kid Batchelor and Tony Addis, aka Mr Addis Ababa and Mr Bang the Party, teamed up to found Warriors Dance Records. From signing a young Jazzie B and introducing dreads to house to producing records by Lee Scratch Perry and SLF (carnival faves KCC), it brought house dub music to the UK. It's one of the most significant centres of black music that Britain has produced and is still going strong.

Can you tell us a little bit about the creative process at Warriors Dance? How did you work together and was it easy? Did you disagree about much musically?

Tony and I were central figures in Warriors Dance’s development and output. Tony and I did not disagree musically? No! He was a huge fan. We were the in-house producers under our aegis acts, such as Bang The Party, No Smoke, Who Kissed The Housemaids, Melancholy Man, James Harris, Mark Rogers, Three Wise Men, Land of Plenty, Cybertron and Soul to Soul, were forged.

As a kid growing up in the seventies, creativity was attached to music. It has since migrated into other areas. Creativity thrives when given a problem to solve, and so many of the constraints of the '70s music technology forced musicians to exercise all their artistic communication skills. As Igor Stravinsky said in 1942, “the more constraints one imposes, the more one free's oneself of the chains that shackle the spirit”. Technological limitations collided with consumer demand to provide a golden age of creativity on popular music.

Music has gone from a handcrafted process to a mechanical one. Back in 1999, commercial hip-hop was the threat. We didn't know all of music would change so much in just 20 years – and life in general. But, really it comes down to whether we are ready to evolve. We're seeing change happen in realtime now, and it's scary to us. Technology already plays a huge role in the writing and recording process. As a Dj, producer, the way I see it from a creative and technical standpoint, we're always improving. But I will say that sometimes too much of a good thing can be numbing. The musical palette I've built for myself allows for a lot more mistakes and grit, and an unpolished rawness. Music is so easy to process and create and perfect now. With the click of a button, the world is your oyster.

Have you heard of Melodyne? If I wanted to take the clarinet out of Stevie Wonder's Superstition, Melodyne provides me with the digital eraser to do it. A friend used it to take an entire Miles Davis solo from a Miles Davis record, and I didn't miss it one bit. Back in the eighties, the future was edits: “OK I'm gonna make a long version of this song!” Now it's like, “I can erase history.” What if that starts to apply to everyday life? It's amazing to me but also scary.

But pop music will endure as a human process. It'll have even more of a hip hop elements. Of all the genres from turntables to Pro Tools, it's always been the most technologically adept. The next generation of that technology is the phone – it'll become the instrument of everything in the studio from beats to lyrics.

Futurologists reckon we tend to overestimate the short term and underestimate the long term. Music and technology goes hand in glove or hand in hand. So I'm going to talk about how technology can make music better.

Can you remember what kind of equipment you were using? Did you find a lot of samples that were used?

Together with my audiophile colleagues I recorded, mixed and mastered dance tracks to form the Warriors Dance catalogue. We scheduled releases of the recording sessions at the end of each session and had the tracks mastered elsewhere (The Exchange, Camden NW1).

Studio Specifications:

The recording sessions took place in Addis Ababa studio, 389 Harrow Road, London W9 via high end professional consoles, Soundcraft mixing desk (as shown in the pics), large Westlake monitors, small studio monitors Yamaha MS10s and Akai multitrack (24-track) two-inch tape machine, we also had a load of outboard (effects), a Vestex (quarter inch, reel-to-reel), and an amazing range of mics to choose from. And a PC programmer for pre production work, off site.

I didn't do much magpie-ing. There is to this purpose a pleasant story of a sample from rap trailblazers The Last Poets some years since. “Tonight I'll be boarding a red-eye heading to New York City once again. I've been going quite often and I like its presence in my life. It's more than a CompuRhythm-78, a sampler, synth and a delay can encapsulate... But Deekay Jones' use of those tools does conjure up some suitable statement about the city, especially what it might have been like in 1983. Pulse of New York was an incredibly well rounded comp that showed the few people that got this disc what New York music was all about. There's also a track from Xex and some foreshadowing of early Jamie Lidell by a band called Bronx Irish Catholics... maybe I'll post more from this later. Right now, I've got to start packing. Wish me a good weekend and if you long for where I am just think of this track.

PS – After some research I think the “New York” sample was from the Last Poets album from a track of the same name. The 1970 release precedes the crappy Billy Joel song New York State of Mind which came to mind for me. The entire sample has way more depth and weight than I had allowed it to have before: “New York is a state of mind that doesn't mind fucking with a brother...” So maybe this track can also be for the anniversary of MLK’s “I have a dream speech”, noting we have made some progress.”

Can you talk a little about the vibe at Addis Ababa studios?

It ain't reggae sure is funky

It was like Cheech and Chong movie, Up In Smoke?! Ha! The vibe was strictly rockers. The Studio itself was a weapon in the hands of engineer Dubfire (Mark Smith). As well as jazz, african (afrobeat) music there was a genuine love for reggae, ska, and soul – it was a real melting pot. With such roots, I ushered in the new Adis era of deep house. Larry Heard’s new way for electronic musicians to speak to their machines – his programmed drums, synthesiser sounds, and bass lines oozed a sweet sadness and depth of feeling that's still radical. The period from 1984 and 1988, was among Heard’s most fruitful, and the songs he released as Mr Fingers during those years provide a template for me and modern house music. Each song was iconic in its own way, from deep house melancholy of Can You Feel It and Mysteries of Love to proto acid workouts. Vocalist Robert Owens recorded an unreleased album at Addis (produced by Band The Party).

As I speak, I'm making a three part radio programme about afrofuturism – such a rich vein for a series, and of course Warriors Dance: an aural history of the groundbreaking label) and Addis Ababa studios (London): Bang the Party, No Smoke, Soul 2 Soul etc. fits right in with the lineage. Incorporating interviews from central figures in the studio’s development and output, the kind of long form piece you find on Redbull Music Academy.

Addis was a really important centre of UK dance music, as they progressed through reggae (Aswad, Shaka, Addis Rockers), African music (Tony Allen, Souzy Kasseya), Hip Hop (Sir Drew, She Rockers, Three Wise Men, etc.) and Soul II Soul, into the amazing output of Warriors Dance, which in some sense brought it all together. More generally, though, I think it tells an important story about the remarkable shifts in black history in London during the 80s and the unexpected ways people from different scenes and backgrounds came onto each other's orbits and collaborated. I'm particularly interested in this as much by the cross cultural traffic around No Smoke/Addis Posse/Bang the Party, to Yello and beyond. It's also a story that's not properly known – certainly not to the degree it should be. There was a legacy in place.

You worked on a lot of remixes, which ones are you particularly proud of? I adore your 5am dub of Coco Steel and Lovebomb – a real all time fave.

People always expect me to choose Feel It which was a hit for Chris Coco. Then DJ magazine editor turned producer was inspired by No Smoke Koro Koro – still rocking dancefloors after all these years – asked me to collaborate as a mark of respect. Bang The Party Bang Bang You're Mine is an enduring dance classic for the ages. Riviera Trax is none too shabby either. But my best work never saw the light of day. Not perusing opportunities; not fulfilling my potential gnaws at me. I'd give everything for another chance, as the saying goes... C’est la vie! Nonetheless, I am pleased. Joni Mitchell was right: you don't know what you got till its gone.

Warriors Dance was almost scarily ahead of its time, particularly in terms of drum n bass / jungle. But it seemed you didn't really get involved in that scene. Were you interested in the later developments you helped kick off?

I am convinced that, Warriors Dance would've transmogrified into jungle, which is sped up reggae, really. I was instrumental in the beginning/conception of Fabric, the nightclub that opened in a former cold storage at Smithfield meat market EC1 in October 1999. Fabric is a temple to Jungle as a sub genre. Warriors Dance also could have, conversely, been a rap label had it continued its trajectory, now that hip hop is respectable.

Tune in to the Kid Batchelor Show on Solar radio, DAB digital radio, Sky Channel 0129. Saturday’s 2–4am.