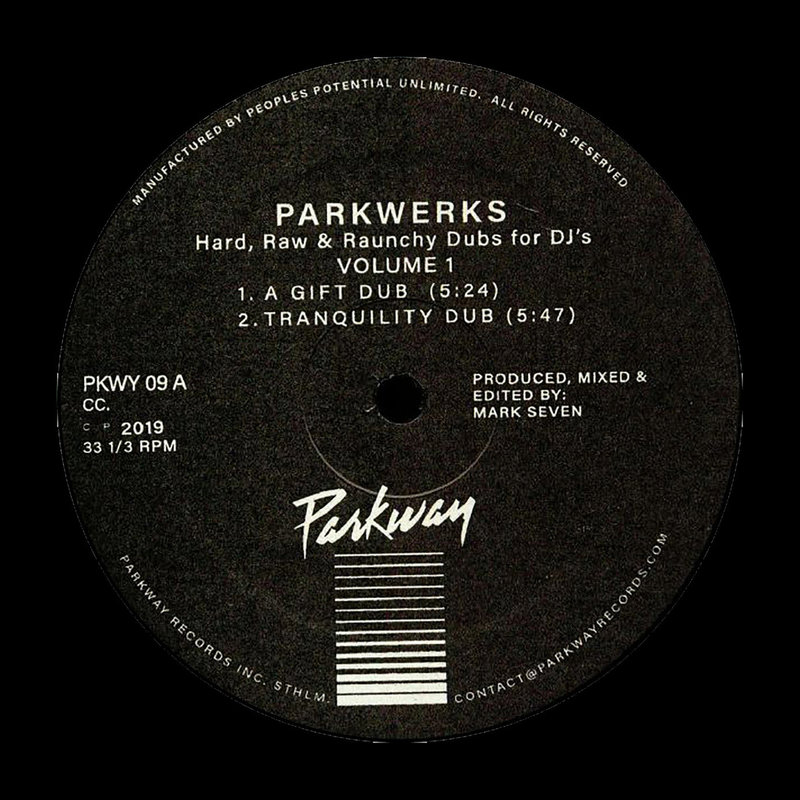

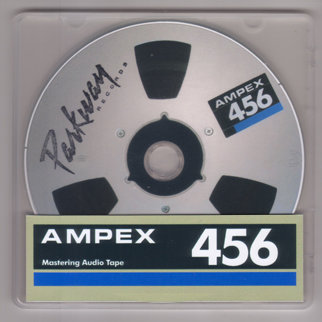

Mark Seven's Parkway Records has just turned ten years old and, while the release rate has been unhurried, the quality control has been exacting. We sat down to chat with Mark about the label's development and where he sees it going next, his journey in music production, and the people and sounds that inspired Parkway.

A lot has been said about Mark's DJ'ing, and I prefer to think of him as one of the finest practitioners of playing records out there, rather than the "DJs DJ." The impact of his Slow Blow mix in the early 2000s was pretty mindblowing, alongside Harvey's Sarcastic Disco. And whilst Mark's sound might seem to have changed, actually, he's more come back to his entry point into dance music, as he discusses in the interview.

He is also a dealer of the black crack. I bought many outstanding records from his Jus Wax store over the years that I can't help but think of him whenever I play them - stuff like Stars N Bars' 'Stars and Bars', Are & Be's 'If There is No Struggle' and that demented gospel house banger on one of the first Parkway megamixes.

If you haven't already listened, I heartily recommend checking out his recent mix for Dekmantel - it's killer!

PH: So the inevitable first question; how has the last couple of years been for you?

MS: I’m tempted to say it's been pretty easy in comparison because, as you're probably aware, Sweden never went into a proper lockdown. So I can only imagine how that was for you, but here things mostly stayed open, although there were some restrictions. I couldn't travel, so I focused on time in the studio.

PH: Are you good at that? Because I think there are different kinds of people. I know people who are super-efficient in the studio, and they can go in and they'll say, right, the remix is going take me a day and a half or two days, and they will do it in a day and a half or two days. But certainly, when I've made music, I needed days of faffing around before any inspiration struck me.

MS: I think I used to be a lot quicker, but then most of the music I made, I'm talking whatever 30 years ago, something, I'd be sitting in a bedroom by a computer and writing something and it is done in a weekend or whatever, but it's never like that for me now. And it hasn't been like that for me for years. I'm not that kind of person that can finish stuff quickly, but I'm really determined, you know? And I really won't let it go. If I think there's an idea there that's worth pursuing, then I'll work at it. In my opinion, too much is made of inspiration.

PH: It's true with anything, I guess, regardless of your mood, if you just sit down and write or make music or paint or whatever, and if set that time aside, none of it is wasted. It's just having the discipline to do it.

MS: I don't know about you, but I, I never had any musical training, so everything comes from ear, and it comes from the inspiration of hearing stuff. But then that takes time, you know, if you don't understand why that chord needs resolving somewhere, then you just have to keep playing until you find what it is. There there's a track I'm working on now, which I've had probably up for six weeks, but I only today found a little bit that pulled the elements together. Before, the feeling was good, and the drums sounded good and everything, but there's a gap in the middle somewhere.

So even though I'm making primarily instrumental music, I have to think, okay, this is where a chorus would be. It's different from techno, where it's just a linear journey. I don't have the luxury of working with a vocalist, and I'm pretty isolated here, so it takes time to get there.

PH: I guess a lot of the stuff you are doing and the things you are inspired are almost like dubs, dubs of vocals, the Zanzibar sound. So do you start from the melody in the studio and work back?

MS: More often than not, a solid bass line. If I find a killer bass line, then I start working around that. There might be an occasion where I find a little vocal snippet and work with it, but mostly it's a bass line then I'll probably build the drums around it. Then I start finding the right chords. It usually goes that way

PH: Would you like to do vocals?

MS: Absolutely. When I started Parkway I had a massive resource of samples to pick from, so finding vocal snippets was easier. I think the voice is really important - you can have great instrumentals, no doubt about it, but when you have a human element, even the smallest hook, the whole thing makes sense. The idea behind Parkway is a continuation of that sound, those dubs, and that club music. But I've always wanted to work with singers and I always hear vocals in my head - mostly it's Colonel Abrams - that's who I hear when I write my stuff.

PH: It's a weird one because I think it's par for the course for people to work remotely now, and it's complicated chemistry happening there. When you are sending a file and you and talk on WhatsApp or whatever, it's very different from the kind of energy you get in a studio.

MS: I understand that. I've had, I've had a couple of experiences where I've had contact with someone and I've sent them an instrumental and they've put a few ideas over. Sometimes it works, sometimes it just doesn't. If you're looking for something in a certain style, a certain power, regardless of how good someone is, they just might not be that person.

I think I’d really need to be in the same room though, you're really putting yourself out there. When you have to sing something you've written it's breaking down barriers and a thing we aren't really used to. It's difficult.

PH: We want to discuss ten years of Parkway, but I wanted to talk a little bit about your journey up to that. I'm conscious you've spoken a lot about the early balearic and acid house days and DJ'ing, but it seems like your production work started a little after that. Were the Lemon Sol records the first things you did?

M7: I did some stuff before that.

PH: Was that more progressive house?

MS: The first proper release was Lemon Sol, but it was done as Bizarre Trax. I got a little disillusioned with what had happened with the whole culture of acid house. I felt like by 89, for me, I'd had enough. So, we did a big party and after that, I wanted to take a break so I went away and traveled in Europe for a while and when I came back, the scene had changed even more. We were not quite at Love Ranch yet, but we were getting there.

There's a lot of leather trousers, and there's a lot of cheeky London geezers. It wasn't the same feeling for me. I was pretty young when it hit at just at the right time when I started going to, to Future and I was really a disciple for it. I felt like this is going to change everything. But after that boom, the comedown was pretty hard

PH: I'm a little bit younger and also not from London, so maybe talking in grossly simplified terms, but it seems there was the acid house explosion. And then, as you say, the London geezer, Love Ranch proggy type thing. And then it kind of split again and that it went broadly into techno or US house and garage. Were you properly into the techno scene, going to the clubs and everything?

MS: Yeah, absolutely, I was immersed in it. I lived in Clapham and I knew Dave Angel who lived in Stockwell so I used to go to his studio and help him out with a few little things like playing keys. I was very influenced by that. I was properly immersed, week in, week out, listening to Colin Faver and Colin Dale. That time was really exciting - it was new boundaries and there wasn't really music before that, that really created that atmosphere, like space travel. We are drifting in space with this. This isn't music that makes you feel like you're walking in fields or sitting on a beach, it's really like out there. It was pretty full-on. I still would buy some other stuff, but not so much at that time. Through those early years, it was pretty much just techno.

PH: Which clubs were you going to? Lost and places like that?

MS: Lost was only just down the road and then I'd follow Dave around wherever he went. We used to travel, he had a mate who was his driver and you'd go around with him and it was mental. The first thing he did when he'd go up to play was take the decks apart - it was like science. He'd get up there, dismantle the decks and adjust the pitch so he could play the records faster. He's doing this and then quickly getting the first record on - he's a beast. I think he's a bit of an unsung hero.

His early music was the closest thing to a British Carl Craig - it was very melodic and he made some beautiful records. He was very influential to me, just his attitude, that it didn't matter about the equipment you had, just whether you had that thing or not. So, to answer the original question, from 92 to 98 it was mostly techno for me.

PH: What happened? Did techno get too hard?

MS: Yeah, techno changed, I didn't change. It’s not me…it’s you!

PH: It feels like there was a gap between the techno and then when you started making music as Mark Seven, but was there still stuff coming out in the interim that I've missed out on?

MS: You haven't missed anything. I didn't make a record for 10 years. I left London in a bit of a tricky state and it was a long comedown anyway, you know, partying and everything that went with it. Half my friends were having panic attacks. I left London with almost nothing. I had a very basic studio left from when I was making music in the nineties and I had no money in Sweden, so I had to sell everything.

Digital was starting to become a thing. Digital studios were really the way everyone was going, so I sold at the lowest probably point. I got rid of my 303, 101, everything. I didn't have any choice. I had nothing I had to live. I started eventually getting some DJ work here, but that was also difficult to get started. I didn't really have any connections so I went around with some tapes. The irony is that I had the Slow Blow mixtape and was giving that out here. I didn't get anything. But eventually, I don't know how, that tape got to someone in the UK. And that was how I found out about DJ History

PH: That's crazy. That's certainly when I first became aware of you. So when you started making music again, was it all digital?

MS: It began with doing some re-edits. The first thing I did my own production on was mostly digital - I think I might have bought one keyboard at that time. That first record after the long break was probably Travelogue, which began as edits and they evolved into musical originals.

PH: And what about now? Is your studio predominantly digital still?

MS: No, much more analog again now. I have two or three drum machines here. I have three or four modules - I have a couple of Junos in here, I have a Korg here, an old Casio. Yeah, I have an analog setup now

PH: The stuff that you are inspired by, compared to disco, it's more attainable as a sound, but it's still the era of really good music musicians and sizeable studio resources. So with people like Timmy Regisford and Boyd Jarvis, there's a real weight to their sounds, and I think you've done a remarkable job of getting there. And it's a combination of both rawness and finesse that makes that stuff sort of work so well. Was it hard getting the sound right?

MS: Every record takes me a long time to get through. We are at 10 years but only 17 releases in, so it's not like prolific. But when I look back on them I haven't put anything out that I have been unhappy with. I'm glad about where we've got by the time it goes out. I think what happened was I really got heavily inspired again by that exact same sound that I started with. It was really that first moment when I left school, I got an apprenticeship, I got some money in my pocket and I would go to record shops. And the records that I remember buying from that time are the records that have now inspired me now.

I remember Touch's 'Without You' was a massive record and Lola's 'Wax the Van', Caprice's '100%". Sleeque was a big record, you know? 'Chief Inspector' was massive. And you're right there's musicianship and certain finesse about it, but it's also the rawness of the equipment. Specifically with Boyd Jarvis because he worked in his bedroom with one keyboard.

PH: Is that right? I didn't know.

MS: He would write stuff and make these tapes and those tapes would be played on Timmys show. That included that first version of 'Running'. He did that at home. So basically those are homegrown and I think that's what inspired me to do the label as well because I looked at those records and I thought this is attainable. Like you say, if you were massively inspired by disco, then you got a long road ahead of you trying to make something that sounds like Vince Montana.

PH: It's not really going to happen.

MS: I mean, there was nothing cynical in that choice of saying, at least I can do this. That was the music that really fired me up. And it still fires me up. I still think records from that time have an energy and the essence of what club music is about for me. It's changed. It's evolved, but it still works.

PH: I'm sure you must have noticed it when you are playing in a lineup with other people, just how dynamically different those records are to modern records. Just how much more range there is in the sound. And sometimes that's actually quite hard as a DJ as well, because everything else is so focused and punchy. The stuff that you play is certainly a much a more expansive, broader sound, isn't it? It's so much richer.

MS: It takes the right environment, you know? Because you have to be able to sort of play, like you say, with a more broad dynamic range and a record, that's maybe gonna break down a little more. It takes the right bill. You can't be playing with people that are there smashing it out.

But I do feel like, over the course of 10 years, I've seen many more people turn back to this sound. One of the things I said when I was talking to someone recently was that this was also a reaction to super-packaged things. And I was guilty as well when I did the Travelogue record - these handmade sleeves and everything's numbered. It just got a little bit too precious, you know? People were blogging about folk music and comfortable shoes and I felt come on, wake the fuck up, you know? It's not over yet!

There was another energy to these records when I listen to them. There's just a basic sort of spirituality and basic energy. It's amazing. I still can't get there, but you listen to some of these records, just the drum intro you feel right away. It doesn't take much, but it takes a lot to get it right. When you listen to something that falls flat, you think, oh, okay, I see what they're trying to do, but this sounds like a modern version.

There's a message there. And over the years of Parkway, I've been able to crystallize the idea more maybe than in the first record. I had an idea, but over time, going through the inspiration and the buying trips, it's managed to crystallize into a more solid idea of what Parkway is. It's still hard to exactly put into words, but it's something along the lines of what you've said, that there's a rawness and there's a more emotional feel to it. This isn't just club music that's there to pound along.

PH: From the outside, it feels like you've created a universe around it. With the design, it looks great; it all fits in so nicely with the press releases and this stuff you send out. It's really beautiful to see that because I guess there are young people who have never experienced it.

MS: I think so. I've done these competitions where I've given away a few things in the last few weeks and some of the people are pretty young, and they've texted me an answer and said, "oh, I didn't know that I learned something," and that's quite nice. It is spreading. You have to be careful with these things, and you don't end up just being a history lesson. But it's nice that people discover it too.

And New York is the essence of it. I don't want to exclude Chicago, but certainly, New York, New Jersey where it was inspired by gospel and disco and with that gay background, but with energy from the new technology, capturing that essence.

Those records are undoubtedly house records - from '82, '83, '84 - they're house. So the model is there already and it's just probably a little more musical than Jack-Jack-Jack to Jack stuff.

PH: Are you still discovering records in that era that you didn't know?

M7: Yes. Not so many amazing ones. But certainly decent, decent records.

PH: I suppose you haven't done it for a while, but were you still traveling to America?

MS: Yeah, I was doing about four or five trips a year for a few years and now I haven't been for two years. A lot of it came from there, but I still find these little things, sometimes they're by artists that have done other things.

PH: It's weird. Isn't it? Obviously, you are deeper into that world and much knowledgeable than I am, but it surprises me. What did I just stumble across the other day? It was an Edwin Birdsong record that's a house tune. I guess it's like you say, there's a load of artists that you predominantly put in another box who in the mid/late eighties crossed over that line into proto-house. But the music never ends, does it? Another door always opens and you're surprised by something else.

MS: It's rare that I find a super gem but now I'm on this journey, I've opened my ears a little more to the freestyle stuff. And a lot of freestyle, I just think it's shite, but some records that come from the freestyle genre are fantastic too. There’s even things on major labels that I just didn't know. I didn't hear it at the time, but you play it and it just fits exactly into this world.

I met an awful lot of really good people as well. The people from that time, that's another inspiration, not just the music. The energy of New York and the energy of those people as well. Because when you talk to those guys, a lot of them are still really buzzy, you know? You just think "you have to be 60 years old and you've got more energy than me!" I met lots of people from the IDRC record pool...

PH: Who was on that record pool?

MS: I met Nelson "Paradise" Roman, Hippie Torales, Aldo Marin, Peter Reyes, and Ray Vasquez. Nelson Diaz who worked for Sleeping Bag - these guys were in the same pool They are great guys, with great energy, just lovely people. That New York energy is fantastic, I think.

PH: You hear people say New York is unfriendly, but I think it's really welcoming. I think a lot of people might have traveled there to pursue something and there's this energy there that is really different to, say, London.

MS: For sure. I've been away from London so it's difficult to say, but, yeah, I definitely feel like there's something crackling there. There are guys that worked for record labels or record stores. I met this fantastic guy that, that worked for Downtown records and he had a great collection, but he was in bad health and he was suffering. You go to 180 something and Columbus or somewhere and go up to their place and they're not in the best of health, but they've still got that energy about them. They're still lively and crackly you know?

The IRDC, that was Eddie Rivera and his brother and they had this record pool that represented lot of Latino American DJs from New York and Jersey and around that area. So maybe not as prestigious as For the Record, but really successful and had some great DJs.

PH: So this is a silly question really. Before I actually looked today, I assumed that every single artist on Parkway was you, but they're not are they?

MS: Yeah, there are some other people that have contributed definitely. Like Joey Beads, The Whole Truth... There are some UK guys, I don't know how much they want to make it public but T-Kut is actually a separate entity.

PH: Right. Would I know them?

M7: Yeah.

PH: Okay. That's really interesting. I didn't know that because I always feel like you're a bit of a lone wolf. Hearing you talk earlier, maybe it was more out of necessity than choice but I see you as having your own world with the label and as a DJ as well. I mean you work with Ari, of course, but sometimes it looks like you walk a lonely path.

MS: In a way, I agree with you, I am. I don't know how that came about - maybe I'm difficult to get along with (laughs). But I think I also don't like to compromise much, I don't mean to sound conceited but I find it hard to take a middle ground. Especially when you have an idea and people are asking you to try it another way.

PH: So you've done ten years of Parkway - what's next?

MS: There's an awful lot more music. As I said, I would like to work with a vocalist, if I could find someone that was local here, and we could go to a place and just build it out. That would be really something. Because there's a limit, you know when I have a track going. I hear stuff in my head, but I just have to try and find a sample that will work, and that that's restricting. I want to take that restriction off and, and just keep doing it.

I would like to broaden, broaden the audience too. Because I feel like the people who have discovered Parkway have stuck with it, but it's still a pretty underground thing. And we get virtually no press, which in a way is quite nice as people discover it naturally and it feels like their thing.

PH: It's like your DJ'ing. It must fuck you off no end, being "your favourite DJ's favorite DJ"

MS: Well, yeah. If you're playing in a room of favorite DJs, there's only 20 of them there, but it's good and bad. You've got to be careful what you wish for because I don't want to change what I do in any way. But I would like to reach more people, so I can concentrate on being creative and doing this all the time, There's a long way to go, but I think I'm getting better and better and there's so much music to make now I've found the essence of it.

I know what Parkway is now. I still feel like it's a modern label, but it's got its roots in another era. Someone asked me what modern house music means now, you know, and I think it's become a mishmash of different inspirations and different eras. You know, there isn't specifically what you would class a modern house sound, for me, there isn't one, and that doesn't necessarily need to be a criticism. We don't have to be like, you know, making robot music or something for it to be modern. But there's room for it to keep growing, and I want to keep going and get better.

PH: Yeah, for me, I feel it doesn't really stop but I have friends who have recently just bailed out They've hit the wall and had enough. I'm really happy to hear you've still got that passion.

MS: No, I don't feel like that, but I can empathize with people who feel the last two years have just finally beaten them. It's just a mission now, you know? Because I think you're right that a lot of people have the motivation when they make music that they want to get DJ gigs. There's nothing really inside them struggling to get out or anything. They just need to let people know they're still available to DJ.

It's very strange mate, because when I think about it ever since the beginning with how the first record turned out, I got ripped off by the distributor and they pressed up loads more than we knew about. People all over the world afterward have come back and said, "do you know what a massive record that was in Holland?"

I just feel like every time I've done something it's sort of been totally missed, where it's not really found its crowd, but it has had an influence. It's been like a crazy almost like a Zelig thing. If you talk about techno, you talk about acid and I'm just… I'm somewhere there popping up in the back while the main players are all going on. The Guerilla records thing, even with LTJ Bukem sampling it. The tentacles have an effect and it all feels worth it.

We asked Mark for a top-five and he came back with some of the key inspirations for the Parkway sound.

The Crossover – there are so many lost gems in that space between the classic boogie era and the takeover of house. This one’s a rough diamond that I used to be able to pick up cheap but then had the Discogs treatment and the inevitable re-ish

Sparkling keys and heavy dubs – so many key records from that era were mastered by Herb Powers, and one of the things I always hear is that brightness on the keys in contrast to the bass. When you can get the sounds right, the dub elements just work.

L-L-L-Love that emulator – I can’t get enough of vocals played across an emulator. Freeeze really set pace with IOU, playing a solo with a vocal sample, but it’s an effect that was used on so many records… like

Raw is good… – One of the inspirations to start the label was how deceptively basic some of these tunes were. Made in little studios with basic equipment, they made me think “I could do this.” But while the elements may be simple, the magic is not. Getting the combination of textures and the lines that grab you, that’s where it gets tricky!

…but well produced can be better! – Ok, whilst the above is true, I’m still trying to make the records sound as good as I can. Some of the studio production from that time just hasn’t been improved upon. The majors released dance dubs with sonics that still stand up 30 years on. Justin Strauss made so many incredible remixes during this time, this one has been a go-to standard for me